Overview

Git is a versioning system with very granular features allowing control over every step of the process. Git commands are divided into high-level (“porcelain”) commands which internally run low-level (“plumbing”) commands. Refer to terminology.

Config

Access the config help menu with git config. You may store any key/value here of format section.key such as portfolio.title, however Git/GitHub will only use a select few when needed. View the global config with cat ~/.gitconfig, and local config with cat .git/config.

Common Keys

user.name- used for author identity for commitsuser.email- used for author identity for commitsremote.origin.url- where repo was cloned frombranch.main.remote- defines upstream

Scopes

--system- system wide--global- user-wide--local- per repository

#VERIFY By default, when using config commands they will assume the--localrepository that you are in. In the event of multiple scopes having the same setting, the more specific scope will take precedence.

Reading/Writing Values

--get--list(or justlist) - rather than specifying a key to view, list them all--set- overwrite the single value--unset--add- for adding additional values, aka. accumulates a value on top of anything that may or may not be there (pretty uncommon)--remove

Repository

A repository is just a folder with a hidden .git directory. Initialize a folder as a repo with git init. Files within the repository will be in one of several states, usually untracked, staged, committed. Half of the developer workflow will consist of git status, git add (to stage), and git commit.

Each commit is logged and associated with a SHA-1 hash identifier. The first 7 characters of the hash can be used to refer to a commit. View commits using git log. These are great commands too:

git log --onelinegit log --oneline --graph --all(ascii graph)

Branching/Merging

Keep track of different changes separately, then combine then back into the base project. These can be done within a single local repo, or between two repos (usually one local one remote).

The standard branch/merge process typically looks like this:

- Update the repository to the latest code (

git fetchorgit pull) - Create a branch for the feature

- Do a couple commits or so

git merge- Remove the branch

Branching

Check current branch with git branch, there will be an asterisk next to it. Create one with git branch <name>. To switch to a new branch use git switch <name>, the older version of the command is git checkout <name>. To create a branch at an earlier commit, specify the hash of the earlier commit like git switch -c <name> COMMITHASH. To delete a branch use git branch -d <name>.

Merging

Eventually we want to merge our branch with the main code using git merge. The simplest type of merge is a fast-forward merge, where the feature branch has the same commits as the base branch, so it just moves the pointer of the base branch to the tip of the base branch without requiring a merge commit. Otherwise, we’ll have to create a merge commit.

Rebase

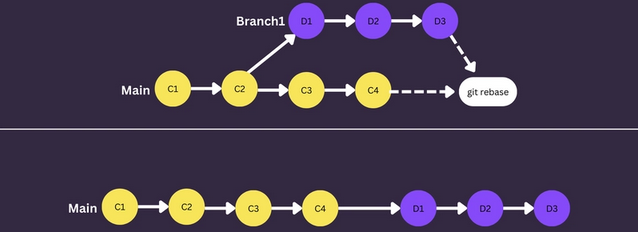

A hotly debated and misunderstood concept. It moves the entire commit history of a branch to the end of the base, allowing for a fast-forward merge. In other words, it’s merge-commit-less.

Let’s say we’re on Branch1 and want to bring changes from main since diverging onto the current branch. When running git rebase main, the following will happen:

- Identify the latest commit on

mainand use it as a temporary new base - Replay each commit from

Branch1into this temporary new base - Update

Branch1to point to the last replayed commit and make this the permanent newBranch1pointer mainremains unaffected;Branch1now includes all changes frommainsince diverging

Warning: Never rebase a public branch like

mainonto anything else, this will cause issues for other developers who havemainchecked out. Typically, the intent is for you to rebase your own branch onto other branches (likemain).

How do I know whether to merge or rebase?

It’s usually dependent on the project; one group may wish to prevent merge commits to promote commit history readability or on the other hand may prefer to maintain a detailed true history of the project. If you want to rebase on every pull to keep a linear history, feel free to use git config --global pull.rebase true.

Undoing Changes

git reset --soft COMMITHASH- goes back to a previous commit but keeps all of your changes (committed changes will be uncommitted then staged + uncommitted changes will remain staged/unstaged as they were)git reset --hard COMMITHASH- DANGER goes back to a previous commit and discards all changes since (cannot be undone)

Remotes

Add a reference to another repo using git remote add <name> <uri>. Traditionally, the “authoritative source of truth” repo (agreed upon to be the most up to date repo) would be referred to as “origin”.

Workflow

Solo

It’s common to just work directly on the main branch the majority of the time. Occasionally open up a branch if desired.

Team

- Update local

mainwithgit pull origin main - Checkout a new feature branch for your desired changes with

git switch -c <name> - Do some work

git add,git commit,git push origin <branch>(not main)- Open a pull request to merge into main

- Review → merge → delete branch

Gitignore

Some files shouldn’t be tracked for a multitude of reasons, usually for bloating and misrepresenting what the actual changes are. Examples include temporary files, hidden files, personal preferences (editor settings), compiled binaries, perhaps files containing sensitive information (although these probably shouldn’t be in the repo in the first place).

To solve this we use a .gitignore file at the root of the project. We can also have additional .gitignore in a subdirectory which only applies to that directory and any subdirectories.

Some patterns are helpful when modifying a .gitignore:

*matches any number of characters, e.g..txtto ignore all text files!negate a pattern to override other patterns, e.g.!important.txtto preserve that file/these are anchored to the directory containing the.gitignore#comments- Order matters, the later patterns take precedence

Terminology

branch- a moveable pointer to a commitmain(master) - default branchfeature/foo- feature branch example

HEAD- a pointer to the current commit/branch being worked on, typically points to branch but can point to commitremote- a reference to version of project hosted somewhereorigin- not a keyword, just a common label for where the repository was cloned from, i.e. “the source of truth”upstream- usually refers to the original repo you forked from, OR the parent branch you’re tracking locallyfetch- downloads commits/branches from a remote without changing the working treepull- fetch + merge (or rebase), updates local branchrebase- rewrites commit history, cleaner than merge but kinda dangerous if misusedmerge- combines changes between two branches, often results in conflicts that need resolutiondetached HEAD- when HEAD points to a commit instead of a branch, commits made here can get lostz

The “Plumbing”

Commits and their data are stored as various objects in .git/objects, you can read them using git cat-file -p <hash>.

Commit- contains a tree and commit related data like authorTree- git’s way of storing a directoryBlob- git’s way of storing a file

Git stores entire snapshots of files on a per-commit level, not necessarily just the changes. However, it still does optimizations to reduce size of the .git folder.